The Apple IIe - Computers Of Significant History, Part 2

Here in Userlandia, an Apple a day keeps the Number Muncher at bay.

Welcome back to Computers of Significant History, where I chronicle the computers crucial to my life, and maybe to yours too. If you’re like me and spent any time in a US public school during the eighties or nineties, you’ve likely used a variant of the Apple II. As a consequence, the rituals of grade school computer time are forever tied to Steve Wozniak’s engineering foibles. Just fling a floppy into a Disk II drive, lock the latch, punch the power switch... and then sit back and enjoy the soothing beautiful music of that drive loudly and repeatedly slamming the read head into its bump stops. Sounds like bagpipes being repeatedly run over, doesn't it? If you're the right age, that jaw-clenching, teeth-grinding racket will make you remember afternoons spent playing Oregon Trail. ImageWriter printers roared their little hearts out, with their snare drum printheads pounding essays compiled in Bank Street Writer onto tractor feed paper, alongside class schedules made in The Print Shop. Kids would play Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego at recess, and race home after school to watch Lynne Thigpen and Greg Lee guide kid gumshoes in the tie-in TV show. Well, maybe that one was just me. Point is, these grade school routines were made possible thanks to the Apple II, or more specifically, the Apple IIe.

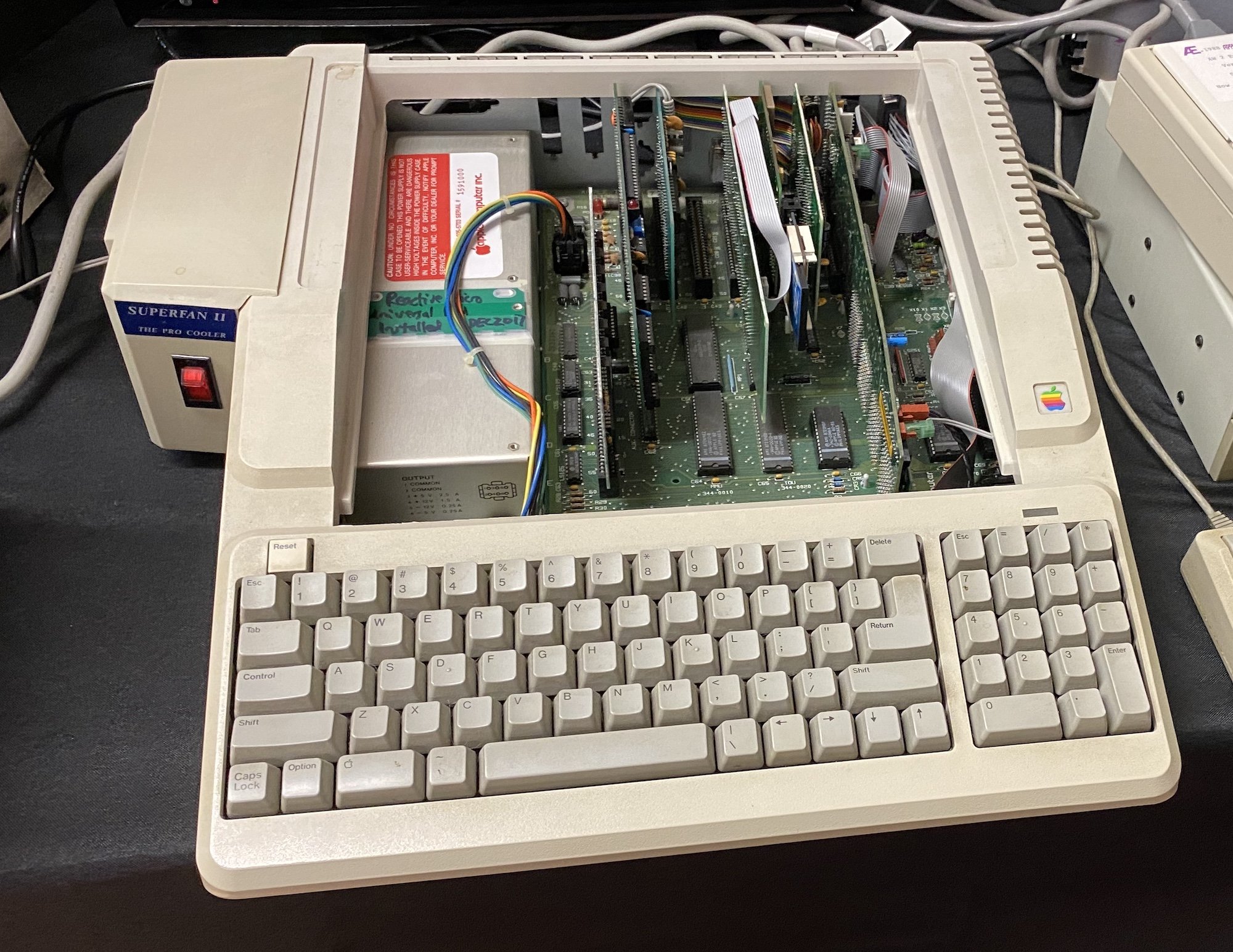

The Apple IIe.

Unlike the BBC Micro, which was engineered for schools from the start, the Apple II was just an ordinary computer thrust into the role of America’s electronic educator. Popular culture describes Apple’s early days as a meteoric rise to stardom, with the Apple II conquering challengers left and right, but reality is never that clean. 1977 saw the debut of not one, not two, but three revolutionary personal computers: the Apple II, the Commodore PET, and the Tandy Radio Shack 80—better known as the TRS-80. Manufacturers were hawking computers to everyone they could find, with varying degrees of success. IBM entered the fray in 1981 with the IBM PC—a worthy competitor. By 1982, the home computer market was booming. Companies like Texas Instruments, Sinclair, and Atari were wrestling Commodore and Radio Shack for the affordable computer championship belt. Meanwhile, Apple was still flogging the Apple II Plus, a mildly upgraded model introduced three years prior in 1979.

Picture it. It's the fall of 1982, and you're a prospective computer buyer. As you flip through the pages of BYTE magazine, you happen upon an ad spread. On the left page is the brand new Commodore 64 at $595, and on the right page is a three year old Apple II Plus at $1530. Both include a BASIC interpreter in ROM and a CPU from the 6502 family. The Apple II Plus had NTSC artifact color graphics, simple beeps, and 48K of RAM. True, it had seven slots, which you could populate with all kinds of add-ons. But, of course, that cost extra. Meanwhile, the Commodore had better color graphics with sprites, a real music synthesizer chip, and 64K of RAM. Oh, and the Commodore was almost a third of the price. Granted, that price didn’t include a monitor, disk drive, or printer, but both companies had those peripherals on offer. Apple sold 279,000 II Pluses through all of 1982, while Commodore sold 360,000 C64s in half that time. In public, Apple downplayed the low-end market, but buyers and the press didn’t ignore these new options. What was Apple doing from 1979 until they finally released the IIe in 1983? Why did it take so long to make a newer, better Apple II?

Part of it is that for a long time a new Apple II was the last thing Apple wanted to make. There was a growing concern inside Apple that the II couldn’t stay competitive with up-and-coming challengers. I wouldn’t call their fears irrational—microcomputers of the seventies were constantly being obsoleted by newer, better, and (of course) incompatible machines. Apple was riding their own hype train, high on their reputation as innovators. They weren’t content with doing the same thing but better, so they set out to build a new clean-sheet machine to surpass the Apple II. To understand the heroic rise of the IIe, we must know the tragic fall of the Apple III.

The Apple III.

When Apple started development of the Apple III in late 1978, IBM had yet to enter the personal computer market. Big Blue was late to the party and wouldn't start on their PC until 1980. Apple had a head start and they wanted to strike at IBM’s core market by building a business machine of their own. After releasing the Apple II Plus in 1979, other Apple II improvement projects were cancelled and their resources got diverted to the Apple III. A fleet of engineers were hired to work on the new computer so Apple wouldn’t have to rely solely on Steve Wozniak. Other parts of Apple had grown as well. Now they had executives and a marketing department, whose requirements for the Apple III were mutually exclusive.

It had to be fast and powerful—but cooling fans make noise, so leave those out! It had to be compatible with the Apple II, but not too compatible—no eighty columns or bank-switching memory in compatibility mode! It needed to comply with incoming FCC regulations on radio interference—but there was no time to wait for those rules to be finalized. Oh, and while you’re at it... ship it in one year.

Given these contradictory requirements and aggressive deadlines, it's no surprise that the Apple III failed. If this was a story, and I told you that they named the operating system “SOS," you'd think that was too on the nose. But despite the team of highly talented engineers, the dump truck full of money poured on the project, and what they called the Sophisticated Operating System, the Apple III hardware was rotten to the core. Announced in May 1980, it didn’t actually ship until November due to numerous production problems. Hardware flaws and software delays plagued the Apple III for years, costing Apple an incredible amount of money and goodwill. One such flaw was the unit's propensity to crash when its chips would work themselves out of their sockets. Apple’s official solution was, and I swear I'm not making this up, “pick up the 26-pound computer and drop it on your desk.” Between frequent crashes, defective clock chips, and plain old system failures, Apple eventually had to pause sales and recall every single Apple III for repairs. An updated version with fewer bugs and no real-time clock went on sale in fall 1981, but it was too late—the Apple III never recovered from its terrible first impression.

Apple III aside, 1980 wasn’t all worms and bruises for Apple. They sold a combined 78,000 Apple II and II Plus computers in 1980—more than double the previous year. Twenty five percent of these sales came from new customers who wanted to make spreadsheets in VisiCalc. Apple’s coffers were flush with cash, which financed both lavish executive lifestyles and massive R&D projects. But Apple could make even more money if the Apple II was cheaper and easier to build. After all, Apple had just had an IPO in 1980 with a valuation of 1.8 billion dollars, and shareholder dividends have to come from somewhere. With the Apple III theoretically serving the high end, It was time to revisit those shelved plans to integrate Apple II components, reduce the chip count, and increase those sweet, sweet margins.

What we know as the IIe started development under the code name Diana in 1980. Diana’s origins actually trace back to 1978, when Steve Wozniak worked with Walt Broedner of Synertek to consolidate some of the Apple II’s discrete chips into large scale integrated circuits. These projects, named Alice and Annie, were cancelled when Apple diverted funds and manpower to the Apple III. Given his experience with those canned projects, Apple hired Broedner to pick up where he left off with Woz. Diana soon gave way to a new project name: LCA, for "Low Cost Apple", which you might think meant "lower cost to buy an Apple.” In the words of Edna Krabapple, HAH! They were lower cost to produce. Savings were passed on to shareholders, not to customers. Because people were already getting the wrong idea, Apple tried a third code name: Super II. Whatever you called it, the project was going to be a major overhaul of the Apple II architecture. Broedner’s work on what would become the IIe was remarkable—the Super II team cut the component count down from 109 to 31 while simultaneously improving performance. All this was achieved with near-100% compatibility.

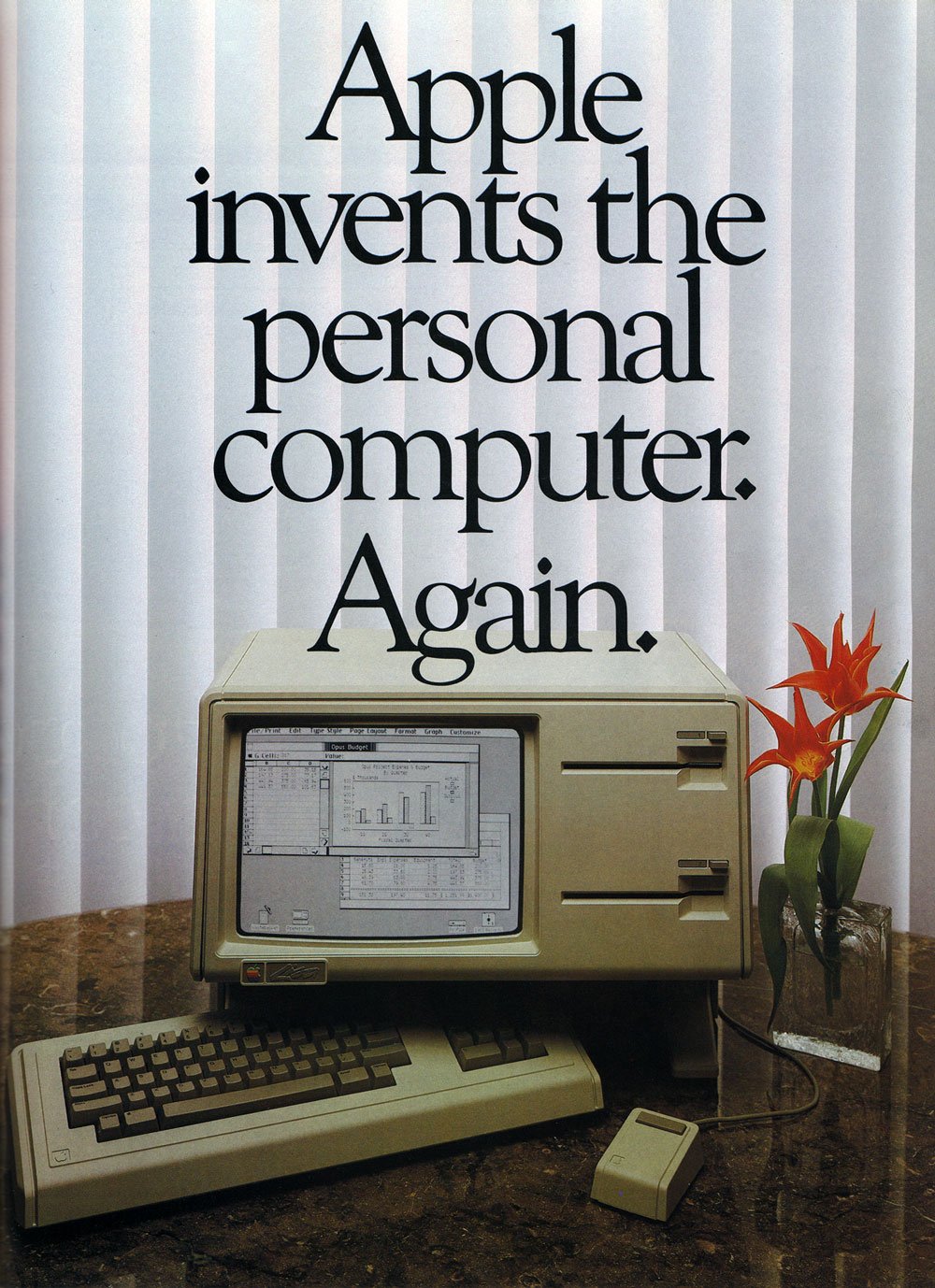

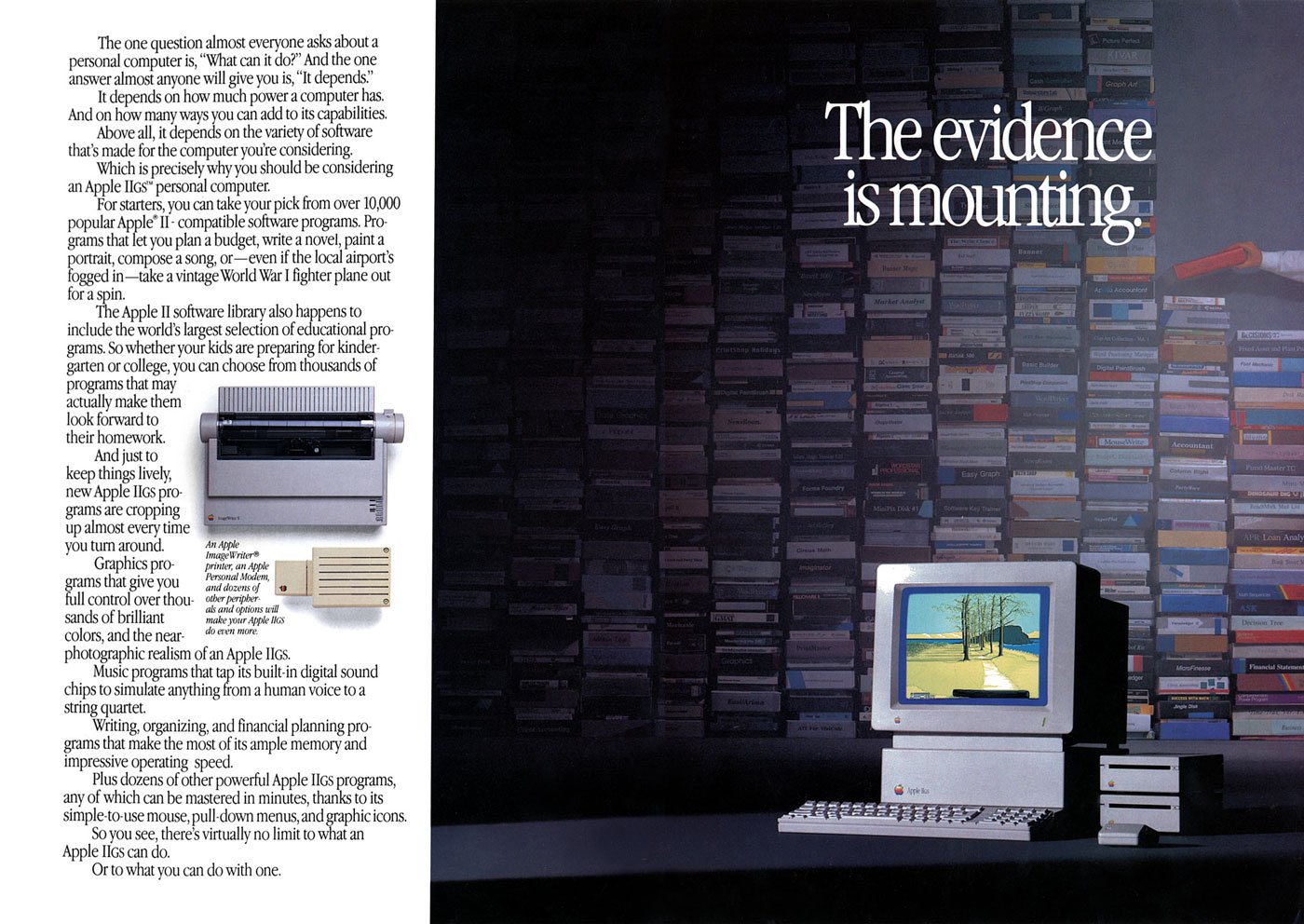

Ad Spread for the IIe

In addition to cutting costs and consolidating components, Super II would bring several upgrades to the Apple II platform. Remember, Apple had been selling the Apple II Plus for four years before introducing the IIe. What made an Apple II Plus a “Plus” was the inclusion of 48 kilobytes of RAM and an AppleSoft BASIC ROM, along with an autostart function for booting from a floppy. Otherwise it was largely the same computer—so much so that owners of an original Apple II could just buy those add-ons and their machine would be functionally identical for a fraction of the price. Not so with the IIe, which added more features and capabilities to contend with the current crop of computer competitors. 64K of RAM came standard, along with support for eighty column monochrome displays. If you wanted the special double hi-res color graphics mode and an extra 64K of memory, the optional Extended 80 Column Text card was for you. Or you could use third-party RAM expanders and video cards—Apple didn’t break compatibility with them. Users with heavy investments in peripherals could buy a IIe knowing their add-ons would still work.

Other longtime quirks and limitations were addressed by the IIe. The most visible was a redesigned keyboard with support for the complete ASCII character set—because, like a lot of terminals back then, the Apple II only supported capital letters. If you wanted lowercase, you had to install special ROMs and mess around with toggle switches. Apple also addressed another keyboard weakness: accidental restarts. On the original Apple II keyboard, there was a reset key, positioned right above the return key. So if your aim was a quarter inch off when you wanted a new line of text, you could lose everything you'd been working on. Today that might seem like a ridiculous design decision, but remember, this was decades ago. All these things were being done for the first time. Woz was an excellent typist and didn't make mistakes like that, and it might not have occurred to him that he was an outlier and that there'd be consequences for regular people. Kludges like stiffer springs or switch mods mitigated the issue somewhat, but most users were still one keystroke away from disaster.

The IIe’s keyboard separated the reset key from the rest of the board and a restart now required a three finger salute of the control, reset, and open-Apple keys. Accidental restarts were now a thing of the past, unless your cat decided to nap on the keyboard. Next, a joystick port was added to the back panel, so that you didn't have to open the top of the case and plug joysticks directly into the logic board. A dedicated number pad port was added to the logic board as well. Speaking of the back panel, a new series of cut-outs with pop-off covers enabled clean and easy mounting of expansion ports. For new users looking to buy an Apple in 1983, it was a much better deal than the aging II Plus, and existing owners could trade in their old logic boards and get the new ones at a lower price.

A Platinum IIe showing off the slots and back panel ports.

Apple might have taken their time to truly revamp the II, but 1983 was a good year for it. Computers weren’t just playthings for nerds anymore—regular people could actually use them, thanks to a growing commercial software market. Bushels of Apple computers were sold just to run VisiCalc, but there were even more untapped markets than accountants and bookkeepers. By 1983, both the mainstream and the industry press had figured out how to explain the benefits of a microcomputer in your home and/or business. Word processors, databases, and—of course—games were all valid reasons to buy a computer, and sales exploded as a result.

Consider Apple’s sales numbers before and after the IIe’s introduction. Ars Technica writer Jeremy Reimer researched estimated sales figures for various microcomputers, and we’ll use them for the sake of argument. For all of Apple’s hype, they sold just 43,000 Apple II and II Plus computers from 1977 to 1979. Radio Shack, meanwhile, sold 450,000 TRS-80s during the same three years. Commodore sold 79,000 PETs. Atari waltzed into the market and sold 100,000 home computers in 1979. One difference is that the Apple II series had a higher average selling price than most of these computers—a TRS-80 kit with monitor and tape deck cost $599 in 1977, while an Apple II without monitor or drives cost $1239.

But this was a time of rapid advancement and innovation, and a hot start was no guarantee of long-term success. The TRS-80 family’s strong start gradually faded away despite newer models with better capabilities, and Tandy shifted to IBM compatibles in 1985. Likewise with Commodore and the PET, which Commodore largely abandoned after the C64 took off like a rocket. IBM sold 1.3 million PCs in 1983 and would only sell more from there. Apple sold 400,000 IIes in 1983, and a million more in 1984, all with excellent accessory attachment rates and monstrous margins. Shipping that many computers with Woz’s original board design would’ve been impossible because Apple’s quality control processes didn’t scale with manufacturing. Between the IIe’s reduced board complexity and new self-test routines, Apple could both build and test computers faster than ever before. With something like a 60% margin on the IIe’s wholesale dealer price, it was wildly profitable—and that was before upgrades and add-ons. With margins like these, Apple could afford to negotiate with schools, and sometimes even give away computers to seal deals.

Not mentioned: Help provided from Xerox.

The IIe wasn’t the only computer Apple introduced on January 19, 1983. Apple management—especially Steve Jobs—were all-consumed with dethroning IBM as the premier choice for business computing, and the Apple II just wasn’t part of those plans. A complex and powerful machine, the Lisa was the talk of the tech press thanks to its graphical interface and forward-thinking document oriented software suite. It was supposed to change the world of computers and singlehandedly make all text-based workstations obsolete. Yet even Apple had to know that, at ten thousand dollars each—in 1983 dollars, no less—the Lisa would be extraordinarily difficult to sell, even though its advanced graphical interface was unlike anything on the market. Another drawback was Apple’s new FileWare floppy disk drives. These drives, codenamed Twiggy—yes, after the British supermodel—were notoriously unreliable. Apple sold around ten thousand Lisas during its lifetime. Meanwhile, the IIe kept on keepin’ on, much to the chagrin of executives who wanted to change the world. Apple finally cracked its next generation computer conundrum with the Macintosh, and they were also hard at work building the Apple IIc and designing the IIGS. Soon the IIe would retire with the original Apple II and the II Plus. Or would it?

An Apple for the Teacher

My memories of the Apple IIe are bound together with its role as an educator. A computer was in every classroom at Highland Elementary School, and as far as my classmates and I were concerned a computer was as fundamental to learning as a textbook or a chalkboard. Like millions of other kids who were tutored by Apples, we had no clue about who designed these machines, or the cutthroat markets that forged them. A school computer was an Apple, just like a school bus was yellow, because that was the way things were. It never crossed our minds to ask why we had Apples at school instead of Commodores or IBM PCs.

By the time Apple launched the IIe, their computers had already found a foothold in American schools. This was largely thanks to the efforts of the Minnesota Educational Computer Consortium, or MECC. Minnesota might not be the first place you think of when it comes to computer leadership, but by the late seventies MECC had brought mainframe and minicomputer access to schools across the Gopher state. Like Silicon Valley and Route 128, Minnesota had a bustling technology and computer center. Control Data Corporation was headquartered in the suburbs of Minneapolis. 3M was a major supplier of materials and media for computers, and the University of Minnesota was full of programmers. When the 1977 trio of microcomputers that all ran BASIC came to their attention, MECC saw an opportunity. MECC’s library of software—called courseware—was written in BASIC for mainframe and minicomputers. Some Minnesota schools already had terminals to access said mainframes, but mainframes were expensive—very expensive. Mainframes also required a staff for maintenance, and they took up a lot of space. Microcomputers solved all these problems—individual teachers could manage them, and they were small and cheap enough to place in every classroom, or even a lab. Since all the new microcomputers used BASIC, it would be straightforward to port MECC’s courseware to a micro—the question, of course, was which one.

Outfitting the entire state school system with microcomputers wasn’t as easy as picking a company and giving them a million dollar order. Rules of acquisition aren’t just for Ferengi—laws dictate how you can spend public money. The first step was acquiring a few computers to experiment with porting their software. MECC was already excited about the new Apple II, specifically for its color video capabilities. They asked if Apple would be willing to cut them a special price for five computers, and Apple obliged. When it came time for the formal bidding process, MECC opened up bids to all comers, but some bidders were better than others. Dale LaFrenz, former president of MECC, recalled as much in a 1995 oral history with the Charles Babbage Institute.

Yes, we got bids from Apple. We also got bids from other companies. Some of the companies, particularly Radio Shack, were not enamored with this process and thought it was kind of hokey—the process being the bid process and the state requirements—and so they weren’t real particular about how they responded. We told Radio Shack, “You know, if you don’t respond in the right way, we can’t accept your bid,” and they weren’t willing to change. The Atari people and Commodore people were late and there were very stringent rules—if you aren’t in by noon on the appointed day, you are [out]. Well, the fact is that the sentiment of the evaluation committee representing Minnesota education was toward the TRS-80.

How different would educational computing have been in America if Radio Shack hadn’t blown off MECC? The bid was theirs for the taking, but for whatever reason, they let it slide. Apple jumped through the hoops, won the bid, and sold 500 computers to MECC. Those 500 computers were crucial to expanding access to Minnesota students, but they were also the base upon which MECC built a software empire. Instead of spending years figuring out what to do with their new computers, MECC ported that existing library of mainframe software to the new Apple II. Word quickly spread and other states and districts knocked on MECC’s door. This ready library of software made the Apple II an easy choice for schools, and launched a virtuous cycle of educational Apple sales. People bought Apples because they could buy MECC courseware, and other developers wrote educational software because the market was Apple. MECC was so successful that by 1983 they transitioned to a private corporation owned by the state of Minnesota, and the Gopher State profited handsomely.

MECC’s early software would be updated and revised and ported to other platforms over the course of the early eighties, but the Apple II would always be its bread and butter. The IIe especially was a crucial ingredient to MECC’s ongoing success as a software powerhouse. MECC’s most popular and memorable titles were either introduced on the IIe or had their definitive versions released for it. Updated classics like the graphical versions of Oregon Trail and Odell Lake required 64K of RAM, which meant a IIe in almost all circumstances. Newly designed games like Number Munchers, Word Munchers, and Spellevator were designed from the ground up for 64K machines. These are the games most people in my age group would have played on their classroom IIe machines in the late eighties on to the early nineties. Though MECC diversified into other platforms, they were still publishing Apple IIe compatible titles well into the nineties.

Apple also updated the IIe during its lifetime, first with the Enhanced IIe in 1985 and then the Platinum IIe in 1987. Internally an Enhanced IIe featured an updated 65C02 processor and new ROMs that brought bug fixes and character updates from the IIc back to the IIe. One such “update” was the MouseText character set, which was used to construct a Mac-ish display using characters instead of bitmaps. Add the mildly updated internals with a mildly refreshed keyboard and you’ve got some mild enhancements. The Platinum IIe was so named due to its new exterior case color, which was a shade of gray that Apple's designers had named "platinum" the year before. The optional Extended 80 Column card was now standard equipment, which brought the total memory up to 128K. The keyboard layout was updated to match the IIGS, which included a standard numeric keypad. Improvements in density meant that eight 8K RAM chips on the logic board were replaced with two 32K RAM chips—Moore’s law in action!—and both ROMs were consolidated to a single chip.

In 1990, the Apple II seemed like a computer Apple just couldn’t kill. They sold over 300,000 across three model lines because schools kept buying the IIe and, to a lesser extent, the IIGS. Schools didn’t want to lose their investment in software, and when a IIe broke, it was easier and cheaper to just replace it with another one instead of a Macintosh or a IIGS. A Platinum IIe retailed for $800, and schools got even better pricing than that. Though the more powerful and advanced IIGS was still a thing, Apple much preferred it when you bought a Macintosh, thank you very much. The new for 1990 Macintosh LC was thought to be the Apple II killer. But even when Apple offered the Macintosh LC to schools at a 50% discount, $1700 was still too expensive for most districts. So they kept on buying the Apple II even if they procured a Mac or two with a CD-ROM drive that might get carted around or parked in the school library.

Still, 1991 and 1992 saw declining sales, and Apple officially discontinued the IIe in November 1993. It outlived its more powerful sibling, the IIGS, by a whole year. Though you could buy a machine labeled IIe for nearly eleven years, it’s hard for me to say that Apple sold the “same” machine for that time. It's the Microchip of Theseus question—does a ROM update, a memory increase, and a new case color really make for a “new” model? Still, the heart of the computer—the 6502 processor, the slots, the logic chips designed by Broedner and his team—was still the same.

Mr. Jobs Goes to Washington

Content warning: this next segment discusses federal tax law. Sensitive readers might want to put on some music for a few minutes.

In today’s world of budget Chromebooks, the idea of the premium-focused Apple dominating the educational market seems quaint. Computers aren’t just one per classroom anymore. Schools are networked now, with devices relying more and more on web services provided by companies like Google and Microsoft. That’s the difference between personal computing and information technology—most teachers could manage a single computer, but you can’t expect them to manage a fleet of cloud-connected services. MECC might have gotten Apple’s foot in the door, but Apple secured their dominant position in schools the same way Microsoft and Google did: good old-fashioned American politicking.

Not every state had an organization like MECC that could advocate for computers in the classroom, so Apple altruistically advocated for them—because we all know how altruistic corporations are. Steve and Steve—Jobs and Wozniak—were true believers. They'd both been using computers since they were young, and wanted to give kids across America the chance to share in the experience. But Steve Jobs also had dollar signs on his eyeballs. And that's why Apple was so eager to work with MECC to supply those 500 computers to Minnesota in 1978, even though that was almost 7% of their sales that year.

Because Kids Can’t Wait to help make Steve Jobs more money.

But getting a computer in every classroom was easier said than done. Even though the microcomputers of the late seventies cost a lot less than their minicomputer brothers, that still didn't mean they were cheap. And obviously, Apple couldn't afford to just give free computers to every single American school. Compounding the cost of computer components were the complexities of complying with the conglomeration of codes that comprise America’s state-based education system. The solution was obvious: federal legislation. If Apple could get a law passed in time for the launch of the IIe, they could capture the educational market with the help of good old Uncle Sam.

As part of the Smithsonian's History of Computing project, Steve Jobs told the story of how he and then-California congressman Pete Stark worked together to draft a bill granting a corporate tax deduction to companies that donated computers to public schools. According to Jobs, there were already tax breaks for companies donating scientific equipment to colleges and universities. But those breaks didn’t apply to primary and secondary schools, which limited the financial benefits for donating computers. Under the proposed law, Apple would donate 100,000 computers, which would cost Apple about $10,000,000 after the tax break. Without the tax break, Jobs figured the plan would have cost Apple around $100,000,000. The bill’s details and failures were more complex than Jobs’ characterization, and I actually dug through Senate Finance Committee and House Ways and Means Committee records to figure out how it worked.

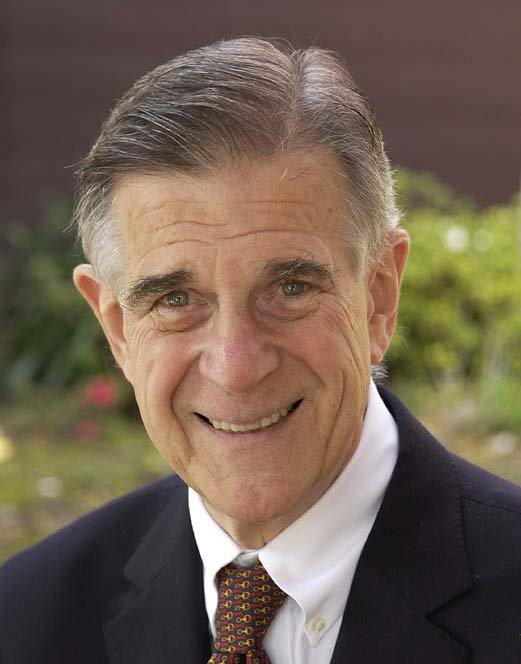

California Congressman Pete Stark.

Stark designed House Resolution 5573 to allow a company donating computer equipment to deduct its cost to manufacture plus 50% of the difference between the cost and the retail price. The total deduction value per computer would be capped at twice the cost. Let’s say you have a computer that retails for $1300, and it costs $500 to make. Under these rules, Apple would receive a $900 deduction—a pretty significant valuation. Multiply that by 100,000 computers, and you’re talking real money. The bill also increased the total amount of money the company could deduct from their taxable income using this method from 10 to 30 percent. Remember, these are deductions, not credits, so it’s not a straight gift. But based on the average corporate tax rate of 42 percent in 1982, the net effect would have been about $90,000,000 over the course of five years.

Jobs personally met with senators and congresspeople to convince them of the need to get more computers in classrooms, forgoing professional lobbyists. Stark’s bill, known as the Computer Equipment Contribution Act of 1982, passed the House with an overwhelming majority of 323 yea to 62 nay, but it died in the senate. Jobs’ recollection of some of the facts was a bit off—he claimed Bob Dole as “Speaker of the House” killed the bill during “Jimmy Carter’s lame duck session.” Bob Dole was a lot of things—professional endorser of Viagra and Pepsi, guest-star on the NBC sitcom Suddenly Susan, space mutant—but he was never speaker of the House. And the 97th Congress’ lame duck session was called by Ronald Reagan in 1982, two years after Carter left office. Dole was chairman of the Senate Finance Committee in 1982, and their report requested a few changes. First, it broadened the definition of educational institutions to include libraries and museums, and it also increased the time period to claim the deduction from one year to three years. But the biggest change of all was reducing the maximum amount of the deduction from 200% of the cost to 150%, and kept the 10% taxable income cap. This change could have reduced Apple’s tax break by 75%. To make matters worse, the other changes could potentially have benefited Apple's competitors.

The US Senate in 1982 was under Republican control for the first time in nearly thirty years, and it was embroiled in all sorts of filibusters and procedural delays. This was especially true in the lame duck months after midterm congressional elections. While Bob Dole’s finance committee was responsible for the changes to the bill, it did recommend that the Senate put the bill to the vote. It’s more likely that majority leader Howard Baker and majority whip Ted Stevens declined to put it on the floor or honor the request to waive certain debate rules. Without some experienced lobbyists on hand to push for their bill, Jobs’ and Wozniak’s dreams of donating thousands of computers went up in smoke. Another angle to this story is the Minor Tax Bills article from the April 1983 edition of Congressional Quarterly Almanac, which is a contemporary take on the events. It turns out Apple itself stopped supporting the bill after the Senate changes, because that would have made the donation plan too costly. But this paragraph got a sensible chuckle thanks to forty years of hindsight.

While the bill was promoted as a boost for technological education, some members objected that it was little more than a tax subsidy for Apple. They pointed out that once the donated computer was in place, a school would be constrained to buy more equipment from Apple, rather than another computer company, if it wanted to expand the use of the machine.

Oh, if only they knew. Even though Apple failed to secure a federal subsidy, they did get a consolation prize at the state level. Around the same time the federal bill fell apart, California Governor Jerry Brown signed a law introduced by California assemblyman Charles Imbrecht that gave a company donating a computer to schools a 25% tax credit against its retail value. In January 1983, Apple announced its Kids Can’t Wait program along with the Apple IIe. Every public school in California with more than 100 students was eligible for a bundle of an Apple IIe computer, a disk drive, a monitor, and a copy of the Apple Logo programming package valued at $2364. Given that the tax credit is based on the retail price, if every one of California’s 9,250 public schools took Apple up on the offer, the total retail value of all those packages would be around $21,867,000. That results in a maximum possible credit of $5,466,750! Apple estimated their cost of the program at around $5,200,000, which included the cost of the hardware, software, dealer training, and dealer incentives. I haven’t been able to find a record of exactly how many schools took delivery, but Steve Jobs claimed every school took him up on the offer. Even if only eighty percent of California schools took Apple’s deal, that would have been over $4.3 million dollars worth of credits on a program estimated to cost $5.2 million. It had to be the cheapest marketshare Apple ever bought.

Apple and congressman Stark did try their national bill again in 1983, but this time it didn’t even make it past the House committee. Sometimes governments don’t move as fast as Silicon Valley would like, but in time other states and the federal government would end up with their own tax breaks and incentives to bring more computers into the classroom. And thanks to the lessons learned from these attempts, Apple’s later teams that sold the Macintosh to colleges were more adept at dealing with governments. By the mid-eighties, Apple was synonymous with education due to the efforts of local educators, governments, developers, and enthusiastic users. They even advertised on TV with music videos set to Teach Your Children by Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young. It seemed like there was no stopping Apple as they sold millions of computers to schools across the globe.

The Head of the Class

The Apple IIe’s long and prolific career as an educator is remarkable for technology with a reputation for a short shelf life. It’s theoretically possible that a first grader who used an Apple IIe in 1983 could use a IIe in 1993 as a high school sophomore. It’d be unlikely, because the Apple II platform was phased out of high schools before middle or elementary schools, but if you told me you were that kid, I’d believe you. The IIe weathered stronger, tougher competition because the hardware was stout and the software library vast. Still, even a high quality textbook goes out of date eventually.

My hometown of Pittsfield, Massachusetts and its public schools hung on to the Apple II well into the nineties, with the venerable system finally being replaced in the 1995-96 school year. Three of the four walls of my middle school’s computer lab were lined with all-in-one Macs from the LC 500 series, and one lonely row of Apple IIe computers remained. Kids who drew the short straws for that week’s computer lab session were stuck in the 8-bit penalty box, forced to endure the same titles they had in grade school while luckier classmates got the latest in CD-ROMs. After winter break, the computer lab rang in 1996 by supplanting the last remaining 8-bit machines with shiny new Macintosh LC580s. Some places held on even longer—I’ve read reports of grade school classrooms still using the Apple II at the turn of the millennium.

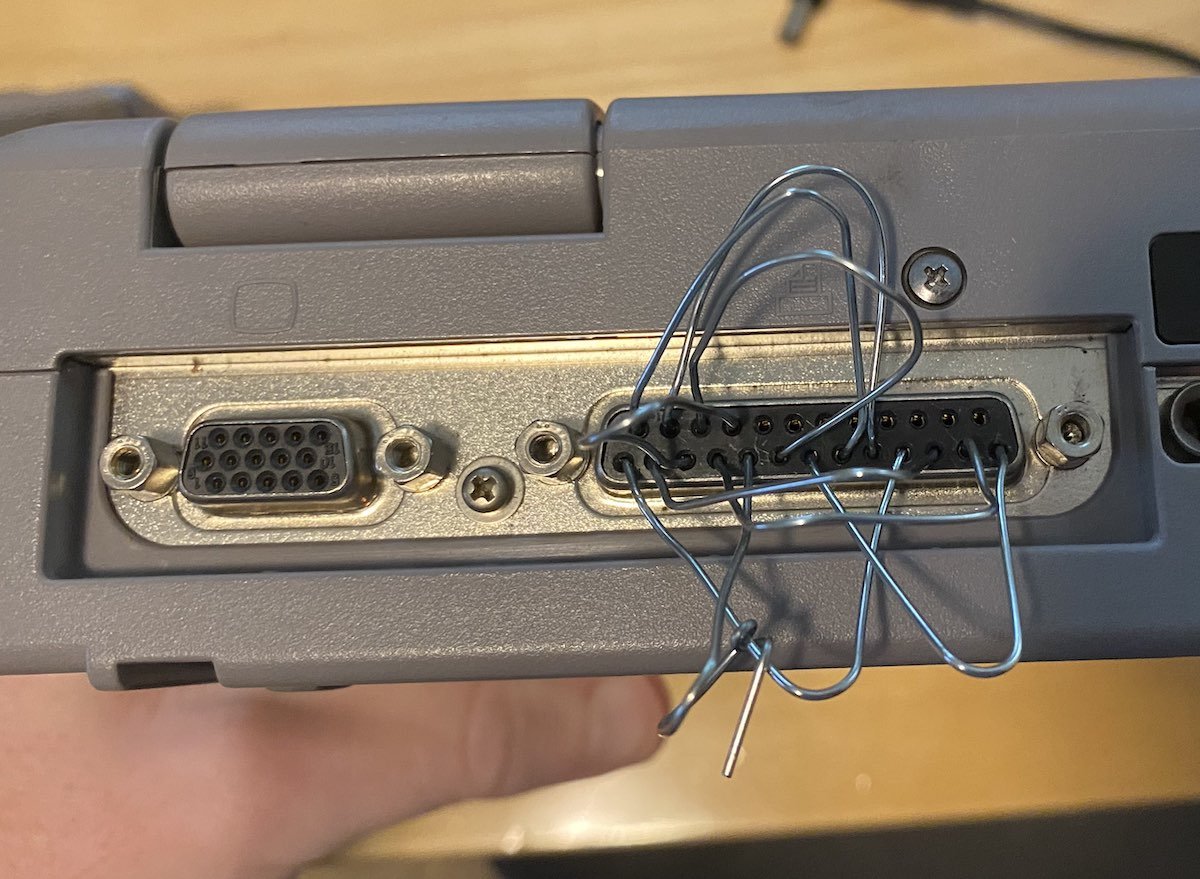

Reid Middle School may have retired their remaining Apple II systems by the fall of 1996, but some vestiges of the old computers lingered on. One day when fixing my seventh grade math teacher’s Macintosh LC II, I noticed something unusual: an Apple II 5 1/4 inch disk drive was attached to it! I knew that Macs didn’t use those old floppies, so I opened up the case to see what, exactly, the drive was connected to. I pulled out the card attached to the machine’s processor direct slot and saw the words “Apple IIe Card” silkscreened on the board. This little piece of hardware was Apple’s way of convincing conservative education customers that yes, a Mac could fit right in. Using tech derived from the IIGS, Apple managed to shrink an entire Apple IIe to the size of a postcard. Moore's Law strikes again. A host Macintosh could run Apple II programs from floppies or a hard disk, and a special Y-cable allowed you to attach external drives and joysticks. It wasn't quite emulation, or virtualization either—if you’re familiar with Amiga bridge boards or Apple’s DOS compatibility cards, it was kind of like that. For the low price of $199, you could make that shiny new Macintosh LC compatible with your vast array of Apple II programs and ease the pain of putting an old friend out to pasture.

The Apple IIe PDS card.

The IIe card was introduced in March 1991, and sales of actual Apple IIe computers plunged. According to Apple, half of the LCs sold in schools came equipped with a IIe card, but actual sales numbers for these cards aren’t really known. The IIe card combined with the ongoing cost reductions in Macs meant the Apple II’s days were numbered. In 1991 Apple sold just 166,000 Apple IIe and IIGS computers—almost half of the previous year—and 1992 declined further to 122,000. Only 30,000 IIes were sold in its final year of 1993. Apple sold the IIe Card until May 1995, and you might think that was the last anyone would hear about the Apple II. Well, it turns out that yes, people still wanted to run Apple II software, and two engineers within Apple wrote a software IIGS emulator. This unofficial project, named Gus, was one of Apple’s few standalone emulators, and it could run both IIGS and regular Apple II software with no extra hardware required. Targeted towards schools, just like the IIe card, Gus kept the old Apple II platform shuffling on for those who made enough noise at Apple HQ.

Most product managers would kill to have something like the IIe—it was a smashing success no matter which metric you cite. Yet Apple always seemed to treat the machine with a quiet condescension, like a parent who favors one child over another. “Oh, yes, well, IIe certainly has done well for himself, but have you seen what Mac has done lately? He’s the talk of all of the computer shows!” The IIe sold a million units in 1984, but it wasn’t good enough for Mother Apple, who kept putting the Mac front and center. Even when the Mac suffered its sophomore slump in 1985 Apple seemed to resent that the boring old IIe sold almost another million units. Macintosh sales didn’t surpass the Apple II until 1988, and Apple didn’t sell a million Macs until 1989. Yes, yes, I know about transaction prices, but that’s not the point—without the Apple II to pay the rent, the Mac wouldn’t have been able to find itself.

I don’t want to judge the Apple II or its fans too harshly, because it’s a crucial piece of personal computing. But I also don’t think Apple was fundamentally wrong about the prospects of the Apple II—they just whiffed on the timeline. The core problem was the 6502 and later 65C816 architecture. Even though faster variants of the 65C816 used in the IIGS were available, the 6502-based architecture was a dead end. Maybe that would have been different if Apple had committed to the architecture with something like the Macintosh. But Western Design Center was a tiny design house operation which wasn’t on the same scale as Motorola, who not only designed their own chips, they fabricated them. Apple’s needs for things like protected memory, supervisors, floating point units, and so on would have meant a move away from 6502-based architectures eventually. A new CPU platform was coming whether Apple II users liked it or not.

The divide between the Apple II and Macintosh is endlessly fascinating to me. Could Apple have made the Apple II into something like the Macintosh? Maybe. The IIGS, after all, runs an operating system that mimics the Mac’s GUI. But what separates the two platforms is more of a philosophical divide than a technical one. The Apple II always felt like a computer for the present, while the Macintosh was a machine for the future. Wozniak designed the Apple II as a more reliable, practical version of his TV terminal dream. The Macintosh was a statement about how we would interact with computers for the next thirty years. Unlike the Xerox Star and the Lisa, an average person could buy a Macintosh without taking out a second mortgage. Other consumer-grade machines with graphical interfaces wouldn’t be out until 1985, and the Mac had the benefit of Steve Jobs’ Reality Distortion Field that let him get away with pretty much everything.

I don’t think Apple expected the IIe to live as long as it did. The IIGS was supposed to replace it—Apple even offered kits to upgrade the innards of a IIe to a IIGS! But the venerable computer just kept chugging along. Unlike the Commodore 64, which was just wearing out its welcome, the Apple IIe aged gracefully, like a kindly teacher who’s been around forever but never quite managed to make the jump to administration. By the 90s, Apple didn’t need the Apple II to survive, so they just quietly kept selling it until they could figure out a way to move everybody to Macintoshes without a boatload of bad press. Maybe it didn’t go as quickly as they would have liked, but they eventually got it done.

What accelerated the IIe's retirement, aside from just being old, was the proliferation of multimedia CD-ROMs and the World Wide Web. The Web was an educational tool even more powerful than a single personal computer, and unfortunately there weren't any web browsers for the IIGS, let alone the IIe. Computers were changing, and computer education was finally changing along with them. Now computer literacy wasn’t just about learning to program; it was learning about networking, linking, and collaboration. A school’s computer curriculum couldn’t afford to sit still, but even after all these years some things stay the same. Oregon Trail is still teaching kids about dysentery, just with newer graphics, nicer sound, and better historical accuracy. Carmen Sandiego is still trotting the globe, both on Netflix and in games.

The IIe was too personal for this new interconnected world, but that’s OK. It did its job and the people behind the first educational computing initiatives could retire knowing that they made a difference. Those classroom Apples taught a generation of children that computers weren’t mean and scary, but friendly and approachable instead. True, any other computer of the day could have risen to the challenge—look at our British friends across the pond with their beloved Beeb. But the IIe managed to be just enough machine at just the right time to bring high technology into America’s classrooms, and its true legacy is all the people it helped inspire to go on to bigger and better things.