The Vintage Computer Festival East 2023 Report

Whirring hard drives, clackety keyboards, and CRT monitors—ah, the sounds of spring. Unable to resist this siren song, certain species of migratory nerds find themselves congregating at the source of this cacophony: the Jersey Shore. Here, in Userlandia, we’re taking a road trip to the east coast’s finest antique computer event: the Vintage Computer Festival East.

Ah, New Jersey. Home of the Devils, Bruce Springsteen, and Rum Ham. My last visit was back in 2021 for VCF East. After missing the 2022 event due to a scheduling conflict, I cleared my calendar to attend in 2023. I enjoyed the vibe of the 2021 show—check out my review from back then—and a five hour drive from my home base northwest of Boston is reasonable for a long weekend getaway. Driving to the show makes it possible to buy or sell big, bulky computers that won’t fit in a carry-on. With a car packed full of hardware to sell in the consignment hall, I set my course to the Garden State and hopped on the highway.

VCF East’s usual venue is the InfoAge Science and History Museums in Wall, New Jersey. Not much has changed since my last visit, and the same rooms (save for one) played their same roles. Hundreds of antique computers and the people that love them congregated in these halls over the course of three days. With exhibitors that exhibit! Vendors that vend! And consignments to consign! So let’s dive in to the highlights, lowlights, and LED lights surrounding VCF East.

Exhibits and Vendors

Flipping through the show booklet or scrolling through the VCF website reveals an impressive slate of exhibitors and special guests. Keeping a show fresh and attracting new visitors without sacrificing its soul is a tough job, but the VCF crew is up to the challenge. By selecting broad themes like “computers in education” and “keeping computing alive” the team fostered a museum road show vibe. Saturday and Sunday promised over forty tables of exhibitors and vendors across three halls. Some familiar faces returned, while others were new to the show.

One thing I appreciate about many of the exhibits is that they’re not just static machines on display, but active demonstrations of what the computers can do. The first hall was a wonderful microcosm of the entire show. Dan Fitzgerald’s Making Music with the Macintosh featured a Mac Plus, SE, and Mini running various MIDI and DAW apps. You could compose and record your own digital music and take it home with you thanks to a giant TASCAM mixing board.

Across the room was Tech Dungeon, selling some Commodore equipment and accessories like their Freeloader 64 cart. For $25 the Freeloader 64 gives you a system monitor, enhanced DOS, a reset button, and fast load functionality. Maybe I’ll write an in-depth review it in the future. Next, Eli’s Software Encyclopedia had hundred of boxed software titles for sale. Three for $20? Sounds like a fair deal to me. C64, Apple, IBM, and Amiga titles were on hand, many still in their shrink wrap. Foenix Retro Systems had a very interesting booth, demonstrating their F256K “modern” retro computer. It’s a system powered by a 6502 family CPU and its own custom TinyVICKY video system. It’s the first I’ve heard of the project, and I liked what I saw. A Fire Emblem-style demo will always catch my eye. Rounding out the room was Cosmic Void, selling some very cool retro hair dye and computer themed accessories.

The next room offered even more systems to play with. Want to read and punch some paper tape? Corey Cohen’s got you covered. Vlado Vince’s collection of eastern European micros gave a glimpse into a world of computing that many of us hadn’t seen. A magnetic core memory demo reminded us what life was like before DRAM and SRAM. The one-two punch of The Unseen World of PowerPC and Workstation Overload featured many expensive machines I only read about back in the day. Alpha, PowerPC, PA-RISC, and more were on tap to show that Intel wasn’t the only game in town.

Eric Rangell’s booth displayed Apple computers used in education back in the eighties. The centerpiece was an Apple IIGS wired to a MIDI keyboard running music tutor software. But just as important was a IIC running Broderbund’s Science Toolkit. Live experiments ran all weekend thanks to working sensors monitored by the program.

The role of Macs in education and edutainment were well represented on the northern half of the hall. Peter and Heather Fletcher’s exhibition on the Living Books CD-ROM series was a nostalgia bomb for people like me who grew up on the cutting edge of multimedia. Across the way was the Macintosh Classroom, a series of Apple computers running learning software and common educational apps. It was like being back in a 90s middle school computer lab, when Apple was the principal computer in American schools.

Southeast Pennsylvania’s Kennet Classic Computer Museum was on the road here at VCF. An SGI Indigo was on hand to detail new museum exhibits and it looked good doing it. Make sure to stop by the next Kennet Classic events in May and September!

I can’t forget to mention the Motorola 88000 exhibit. One of the rarer RISC chips, it’s hard to find working examples of these machines. In an alternate universe, this is what Apple switched to instead of PowerPC.

Dave from Usage Electric had some of his antique terminals and tubes on hand, along with a teletype that could have been ripped from the pages of a steampunk comic book.

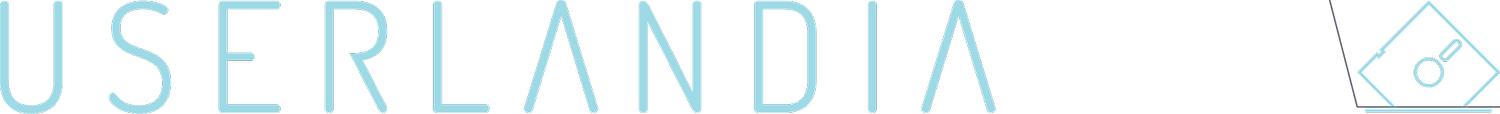

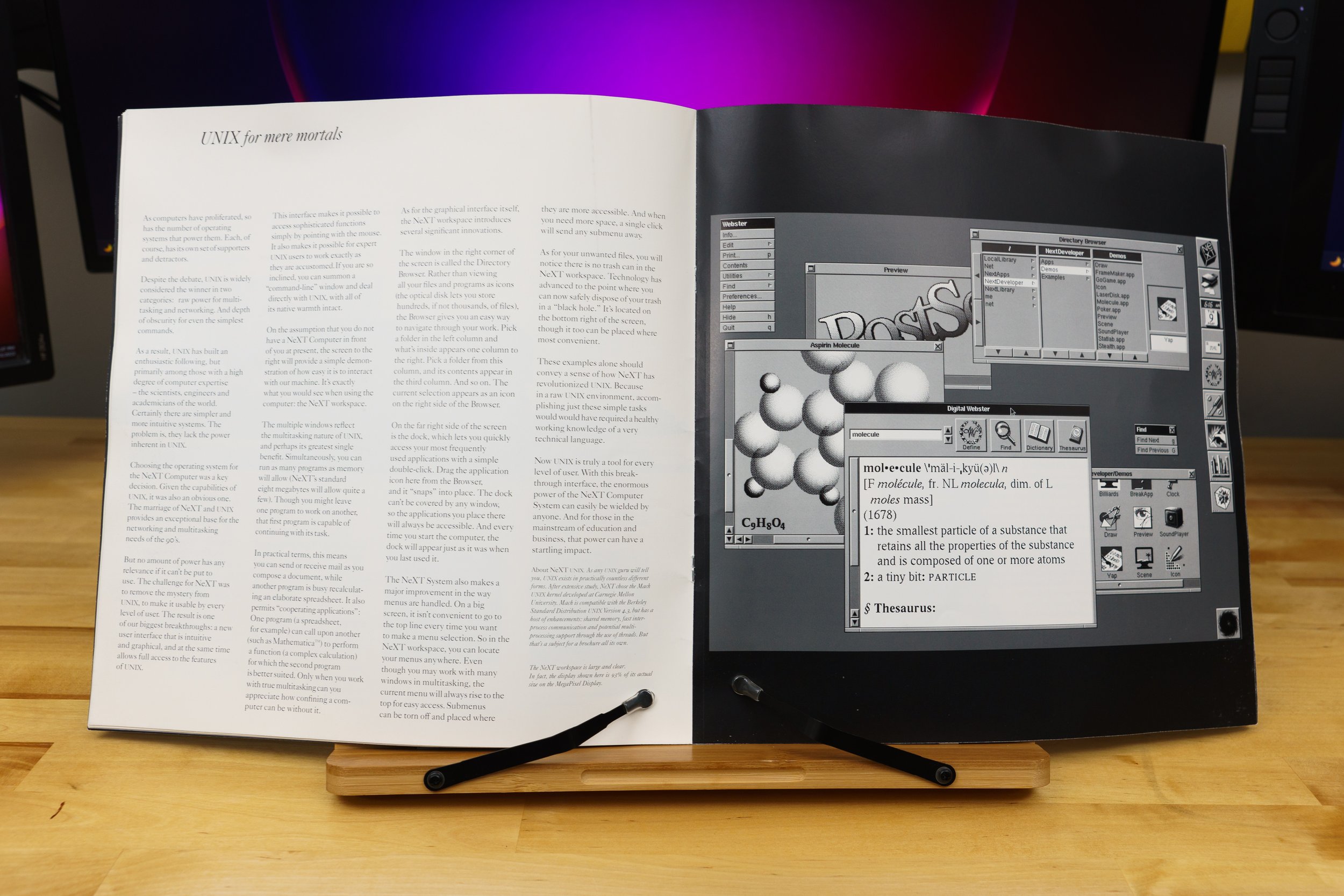

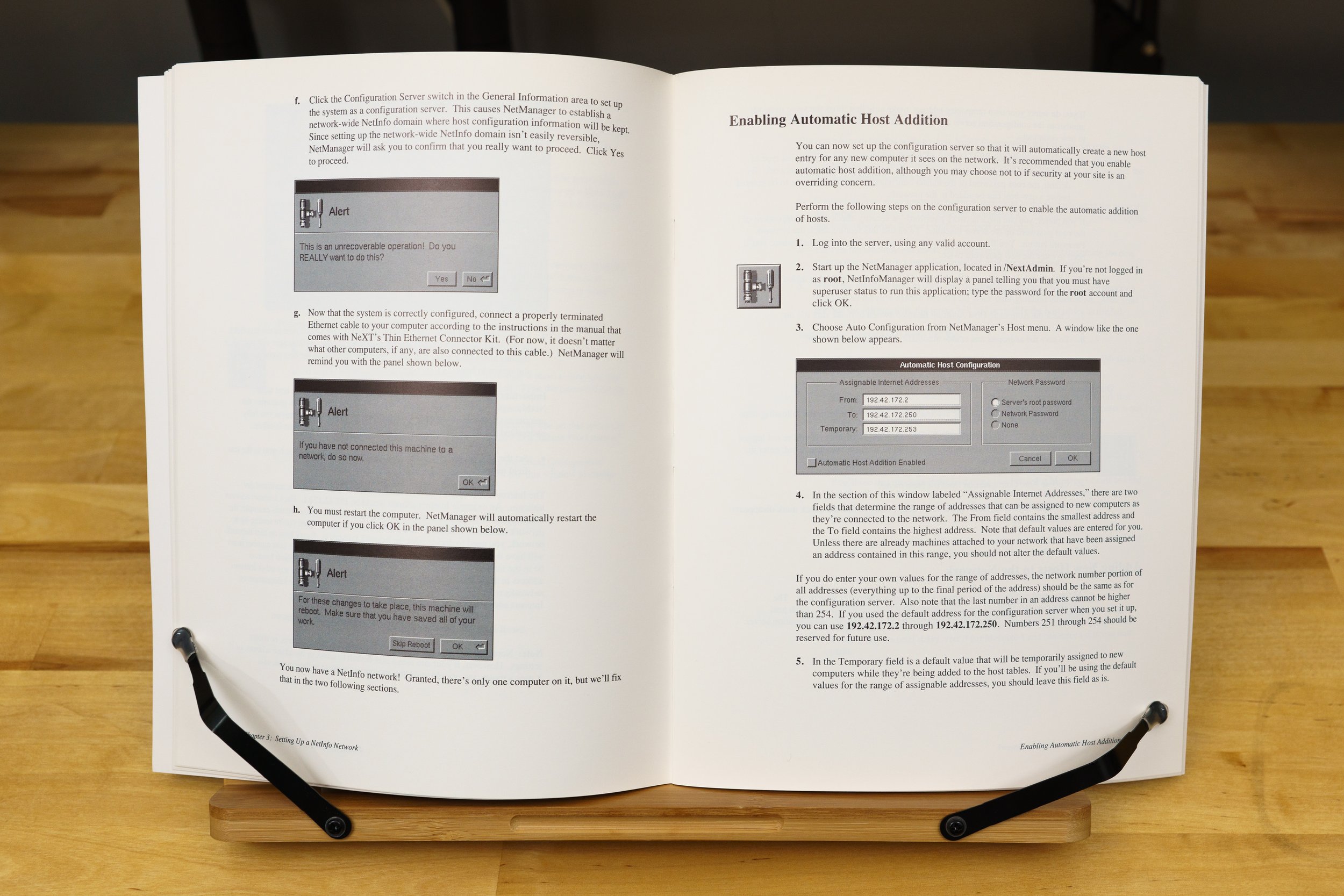

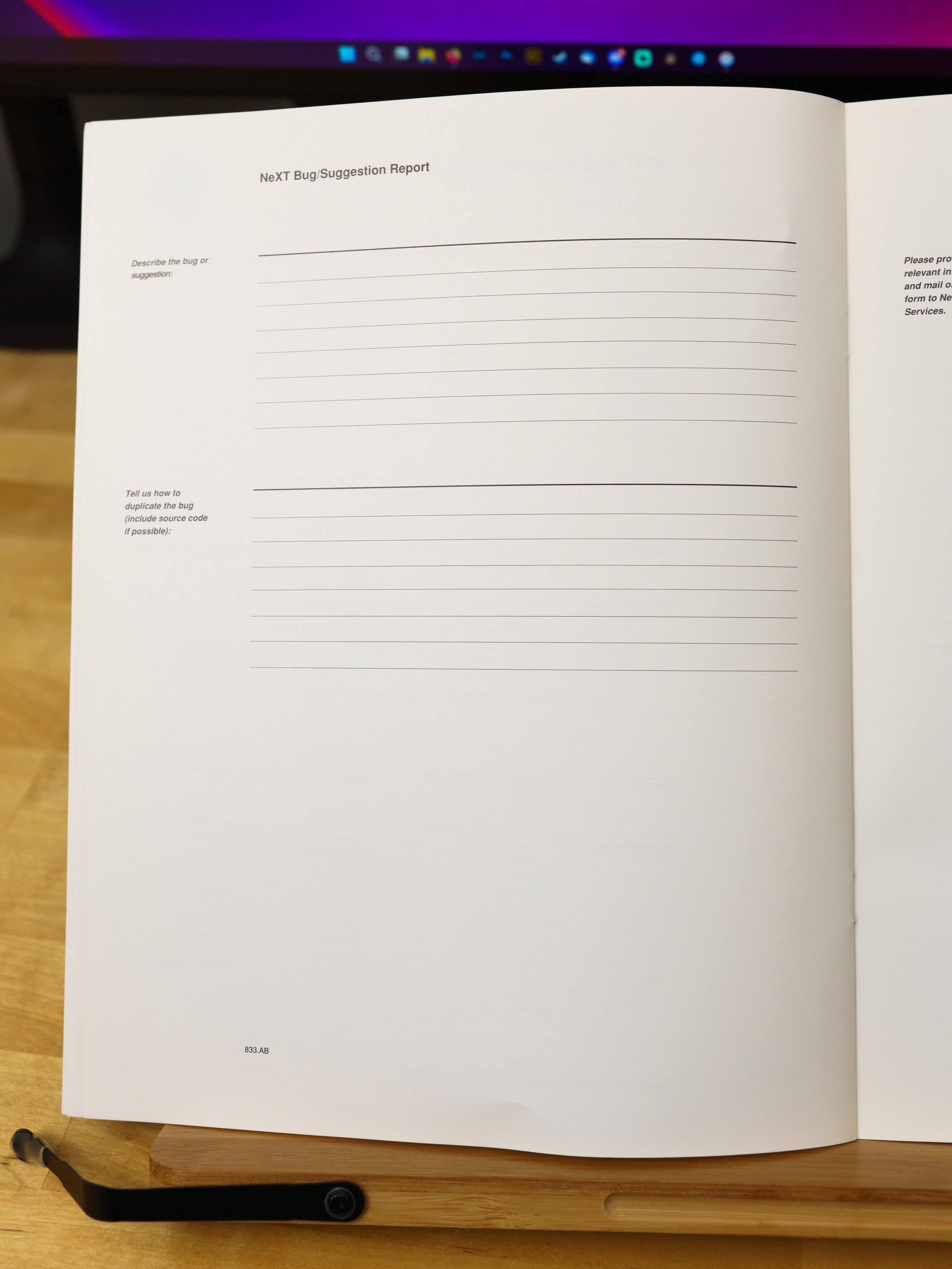

The other main exhibit hall was jam-packed with even more variety. It also had its own array of workstations, featuring 50 Years of Unix by System Source. It’s the greatest hits of workstations by Sun, NeXT, Apple, HP, and more. An Apple Workgroup Server running A/UX, a BeBox that seemed a little out of place, and SGI workstations rounded out this colorful clique.

You might remember the hype surrounding Ken and Roberta Williams’ virtual reality remake of Colossal Cave Adventure. It’s not just hype anymore—the game was released earlier this year! Marcus Mera had a full VR setup for you to try the game, as well as an exhibit celebrating its journey from text to VR. If the VR headset was too new for you, then you could play along with a teletype machine in all its clattering glory.

Working Digital Equipment Corporation into the education theme isn’t as tricky as you’d expect. Indeed, Ethan Dicks’ DEC in Education exhibit had a learning PDP-8 and some fun DEC workbooks to teach you about mini computing. Once you’re done with your lesson, you can get your photo taken and converted to ASCII art at the PDP-8 photo booth.

SGI also had some serious representation, with several booths showing various SGI systems and applications. Multiplayer Quake was on hand, along with Alias demos and the SGI Web.

Alastair Hewitt is back again with his TTL logic computer, now with many upgrades and improvements. This time I didn’t forget to bring my LaCie ElectronBlue monitor hood for his monitor! My monitor may be long gone, but his monitor is now complete.

RetroTech Chris’ IBM Classroom had a full network setup featuring IBM’s Classroom LAN Administration system, or ICLAS. This might be the only operational Token Ring network I’ve seen in person. Props to the PS/2 Model 30 286—I’ll get one back again some day!

You might remember Behind the Screens, the folks who preserve old Weather Channel and Preview Guide systems. They were out in full force, and they’ve expanded a bit. Want to know how cable scrambling worked? It’s right there! Just, uh, don’t tell ASCAP about the live performances of music videos.

I also spent some time talking to Dave from Dave’s Retro Video Lab about his collection of vintage camcorders. Despite the fact that I’m producing videos these days, I don’t really consider myself a “video guy”—it’s never been my forte, and I’m usually more comfortable with audio and writing. But Dave and I had a great chat about the invention of electronic image stabilization and our struggles with “doing it live.” His enthusiasm is infectious and his live stream of the event is worth checking out.

Friends of the show Steve from Mac 84, Sean from Action Retro, Ron from Ron’s Computer Vids, and Mike from Mike’s Mac Shack were all gathered together at their Totally Normal Computing table. Their greatest hits were there, like Mike’s prototype iMac G5 and Shaun’s cursed SE/30, but they brought some new material as well. The Apple I replica attracted a lot of attention, as did the ImageWriter LQ and the 20th Anniversary Macintosh G4.

Want to see how digital retouching and painting for video was done before we had Photoshop on commodity hardware? Adrian Wilson presented a working Quantel Paintbox, which allowed many attendees to give live demonstrations of their artistic abilities.

If you’re a TRS-80 fan, then you’ll love Mike Lowen’s Tandyland. S-tier name, no notes. A TRS-80 timeline from the 1977 original all the way up to the mighty model 4P celebrated the life and times of a foundational microcomputer.

Lastly, a big shout-out to Amiga of Rochester, Retro Innovations, and DosDude for performing live repairs, custom board assembly, and upgrades. One such upgrade was soldering G3 CPU upgrades in ball-grid-array Mac logic boards. Turns out that you can upgrade many 604 Macs to a G3 processor if you can solder ball grid array chips! I happened to catch one of these upgrades live, and he made it look so easy. Don’t try this at home, kids.

Panels and Guests

Scheduled along with the exhibitions were three days of talks, classes, and special guests. Hands-on learning has been a part of the Federation’s mission for years now, and the tradition continues in 2023. A learning space dedicated to Commodore computers was one of the headline events for this year’s show, and it didn’t disappoint. Beginner and advanced classes on Commodore BASIC and assembly language were available on all three days to teach you how to keep up with your Commodore. Learning about Commodore wasn’t limited to programming, either. Dave McMurtrie of commodore.international hosted history classes where you could learn about the business dealings of Jack Tramiel and company.

Next door in the Computer Deconstruction Lab was a mini-repairathon as well as build-your-own-board sessions. XT-IDE kits were on hand along with other projects to test your soldering skills. Don’t worry if you don’t know how to solder, because classes were available to help teach you how to wield an iron.

All three days had a jam-packed panel schedule. You could spend eight hours a day watching all the talks, with subjects ranging from the Apple Lisa, the Nabu, computers in schools, and advanced C64 sprite programming. Unfortunately I missed most of Friday’s panels, which means I’ll have to catch the VODs that the Federation conveniently posts on their Youtube channel. I did catch the Friday Streamer Roundtable, featuring Adrian Black, Jeri Ellsworth, David Lovett, and Fran Blanche. Casting Bill Herd as the moderator was a brilliant choice. I love Bill’s candor—he’s able to get away with some good-natured ribbing, especially with this group of guests. Bill also hosted Saturday’s roundtable, which featured David Murray (the 8-Bit Guy), Steve from Mac 84, Sean from Action Retro, and Mike from Mike’s Mac Shack. Both panels were worth attending as the guests had very different answers to Bill’s questions.

My favorite non-roundtable panel award goes to Jeri Ellsworth. Retro nuts know her best as the wizard behind the C64-on-a-chip found in the C64 Direct to TV joystick. But that device is only part of her story. She told tales of her time as a computer shop owner, race car builder, and augmented reality startup CEO. I highly recommend checking out the VOD once it’s live.

Consignment

One of the big draws of VCF East is the consignment hall. It’s open to anyone willing to schlep their stuff and fill out a form. It’s like stepping back in time to an old computer store, which means you can see some seriously cool stuff. At previous shows I’ve arranged some trades ahead of time with other attendees, but this year I decided to try my luck as a seller. Overall the consignment sales experience was excellent, with only a few minor hiccups that were handled by the VCF team.

Life as a seller starts with signups. Back in 2021, you had to list your items for sale on a paper form. 2022 overhauled the process by introducing an electronic inventory system and bar code price stickers. This carried forward to 2023 and it was a pleasure to use. After sending an email expressing your interest in consignment, the staff replied with a Google Sheet linked to their inventory system. All I needed to do was itemize my items, proclaim my prices, and quantify my quantities. At check-in the staff printed out a string of price stickers using that spreadsheet data. When the barcodes are scanned, the point of sale system looks up the price and seller info. This makes tracking who sold what and how much they’re owed a breeze. Checkout and payments are handled by VCF staff, saving consignors from babysitting their wares.

Not that I would have been able to babysit anyway. Unlike 2021, which hosted the consignment in the large open hall in building 9010-C, 2023’s consignment was in the two adjacent cafeteria rooms. Apparently this is because that hall is under renovation. These smaller, cramped quarters meant a maximum capacity of 25-ish people, and that meant a long wait just to browse. If you weren’t in line first thing in the morning, then you were going to miss out on some of the unique items for sale.

Being a consignor also grants some advantages as a buyer. After bringing in my items, I was able to browse around and see what’s for sale. There were some legit deals on those shelves. I bet this $100 A600 was bought by the first person in line. But what caught my eye was a Compaq ProLinea 4/33. If you’ve read my Computers of Significant History about this machine, you’d know why I want it. $70 was a reasonable price and I knew I had to get in line early to have a good chance at buying it.

I joined the line on Saturday at 8:30 AM in preparation for a 9 AM opening. By any reasonable measure I had a decent spot in line, and I was in the room by 9:30 or so. Fortunately nobody had snagged the ProLinea, so I was able to bring it home. My buyer’s experience was painless. A Square cash register meant customers could pay with cash or cards, and the barcode scanning made checkout a breeze. The easier it is for people to buy things, the easier it is for consignors to make money, and the easier it is for the show to earn a 15% commission.

There were hiccups and adjustments, of course. Most were born from good intentions. The free pile was originally located in the corner of one of the consignment rooms. Between the crowds and issues with checking receipts, it was eventually moved outside. Good thing it didn’t rain during the day. This change wasn’t immediately obvious, since there was no signage or announcements, but consignment staff informed people when asked.

Another inconvenience to shoppers was a perk for others: the consignment hall closed for an hour or two to serve lunch on Saturday. That’s because lunch was served from inside the hall. I believe this food service is in partnership with the JROTC or something, as I saw volunteers serving various foodstuffs from the larger consignment room. I overheard grumbling from various attendees about this, and I see both sides of the argument. On the one hand, offering lunch for sale is a great idea because there’s not much around for food unless you want to give up your parking spot and drive off the campus. On the other hand, the crowd was enormous and losing a chunk of the day to browse and buy might have messed with your availability for shopping. Still, VCF did what they could within the constraints put upon them. An outdoor food tent for the volunteers or a food truck would be a good idea. I also didn’t really like the idea of food mixed in and around stuff for sale, but as far as I know there were no spills or disasters.

I did have one consignment problem during the weekend. One of my items for sale was a Sun Ultra 10 workstation with various accessories included. Sometime on Saturday the matching keyboard and mouse disappeared. I only noticed this late in the day because I was busy at panels and couldn’t really check the room due to the long lines. I notified the show staff, who made it a priority to find the missing items. Luckily, they did—the keyboard and mouse were reunited with the tower before the hall opened on Sunday morning. The system eventually sold later that day. I can’t thank the VCF staff enough for taking the problem seriously and saving the day.

This leads to another tricky part of consignment, and that’s item lots. I had two lots to deal with—the aforementioned Sun workstation and a TI-99 collection I was selling on behalf of a friend. The TI-99 was easy enough—I had the machine and a box of software and accessories. I attached a readme and price tag to the box, and set the computer next to it. Seemed fairly obvious that they went together. With the Sun, I laid the accessories on top of the case. In my mind, this implied they went together, but I can see the ambiguity there. I want the accessories to be seen to increase the attractiveness of the lot, but with the way things were laid out on the shelves it’s hard to tell where one group stops and another begins. I’m not sure of a good way to improve this, other than to use more readies and tape and boxes to keep everything together.

Another conundrum is dealing with the rush. Given the number of Saturday attendees this year, there still would have been lines and wait times if the larger hall was in use. But with how tightly packed the merch was and how few people were let in, the whole thing had a Black Friday kinda vibe, and I don’t think that’s the atmosphere the show runners were angling for. I hope there isn’t an escalation of either camping or backroom dealing in our future. That said, the lunchtime break did have one benefit: it cleared out the line, which reset the vibe of the room.

My other points about consignment are more towards fellow sellers and, to a lesser degree, buyers. I’ve done a lot of conventions where I’ve tabled and sold things, and the key to making sales is knowing your audience. I saw a lot of Mac Pro towers, and the vast majority didn’t sell. Odds were that they were asking for too much money, but let’s be honest: people aren’t going to this show to buy ten year old Xeons. Haggling was an option, but that required getting contact information from the volunteers. I bet most buyers didn’t even know that was an option. If you’re a seller open to negotiations, I’d recommend attaching signs with your phone number to your items. Most consignors who wanted to cut prices opted to update their spreadsheets and print new price labels on Sunday morning.

Another piece of advice: don’t bring a bunch of late-model office or home PCs. They might be useful to somebody, but it’s not in the spirit of the show, and it’s no surprise there were still a bunch around at the last call. I saw a lot of plasticky Pentium 4 Dell towers and late aughts HP boxes from various sellers. Now, I know a decent number of them sold, but the leftovers implied that supply far outstripped demand. These machines have very little collectible value at the moment. Of course, we said the same thing about Pentium MMX PCs a decade ago. Just give it time.

What about pricing? Most of the gear ran the gamut from “bargain” to “expensive but fair.” I think the most expensive item was an Amiga 4000 tower with a Video Toaster and some accouterments which stickered at $3,000. Yes, that’s a lot of money, but given that they’re generally unobtanium, I’m willing to allow it. One of the gotchas of trading in vintage gear is that you might have something that’s rare, but if you don’t have a buyer, then it doesn’t matter what it’s valued at. The guidelines warned that eBay prices were “too high,” and I think most people heeded that warning. You also have to factor in the show’s 15% commission into your price, which I think is a fair take. Everything sold at the consignment hall benefitted the Federation in some way—not a bad idea for a fundraiser.

I think people like using these events as an opportunity to pass gear along to someone who needs it. If you bought something with the intent to flip, you’re bad and you should feel bad. That’s why I’m glad when good people find a good bargain. A great example is this Macintosh LC 575 picked up by Ron from Ron’s Computer Vids. It was tucked away with the faceplate off to the side, and the price label listed the Apple ML model number, which most people don’t understand. A perfect recipe for being overlooked until noticed by a discerning eye. The machine powered right up to a desktop with no problems whatsoever. Maybe the person who brought didn’t have an ADB keyboard and didn’t know about soft power. Had I seen it, I would have bought it. For only $85, this was an incredible bargain, much like the $100 A600. Good find, Ron!

Things slowed down as Sunday wore on. Some otherwise decent machines didn’t sell, either because they were spendy or a little niche. Still, I don’t think anyone was unhappy with their experience. The only thing of mine that didn’t sell was an old boat anchor dual socket Pentium III Dell server, and it was kind of a reach anyway. Getting paid was easy too. Give your name to the staff, they look up your sales sheet, and print it out. After signing with your John Q. Nixon you can request Venmo, Paypal, or cash monies. Aw yeah.

The Experience

As I wandered around the show, I heard some chatter that their Eventbrite presale numbers were more than triple the previous year. The number was somewhere in the range of 650, and that didn’t include at the door tickets. I totally believe it, especially on Saturday. The main exhibit halls were crowded with people, and latecomers on Saturday had trouble finding a parking spot. Sunday was considerably less busy, which made it easier to explore and spend time with the various exhibits. There was still plenty of people, but it felt far less claustrophobic.

What did I bring home from the show, you ask? Unlike VCF Midwest, where I went all-out on that NeXT kit, the neat and weird stuff I would have bought (like the Amigas) were all gone by the time I made it into the consignment hall. I picked up the ProLinea and a $3 new-in-box Compaq keyboard, both of which will be featured in an upcoming video. The Freeloader 64 cart was the other tech item I bought. I also bought a few T-shirts, including the C64 one that I missed from last year’s show. T-shirts and other VCF merch were on sale next to the consignment register, which also has its pros and cons. Yes, you have to wait in line to get into consignment, but I think it’s great for impulse buys—might as well get a shirt while you’re buying a computer, right?

What does the future hold for VCF East? Crowd management has to be high on their list. I’m not sure if the growth trajectory will continue like this, but if Eventbrite pre-sales look similar for next year’s show they’ll surely make some adjustments. I’m sure having some very popular YouTubers on hand goosed the number, as people around here rarely get the opportunity to meet David Murray or Adrian Black. I heard a few people saying that attendees “should really consider some of our other events” like the swap meets, but unless you’re within day trip distance it’s tough to justify the swap meet, especially if you’re east of New York. If I were to go to the swap meet, I’d have to spend a minimum of two tanks of gas (probably $90), $30 to $40 worth of tolls, and a $150 night at a hotel for the chance of finding something interesting. And that isn’t even talking about the traffic. There’s also no guarantee that there would be stuff I’d want to buy, although I’ll grant that the odds are very good. It’s a lot easier to justify that kind of expenditure on a long weekend with a lot of events.

Yes, consignment and trading equipment is a large part of the show’s appeal. But visitors want to see the panels, they want to see the exhibits, and they want to talk to the guests. The venn diagram of people who would go to the swap meets or smaller events doesn’t completely overlap with a VCF crowd. I saw license plates from as far away as Washington—jury’s out on whether they were rental cars.

But in spite of the crowds, the lines, and the cost, VCF east was a smashing success. The best part of these shows is always the people. I owe a lot of thanks to Steve, Mike, Sean, and Ron for letting me be part of the Macinsquad, as I dubbed it. Friends don’t let friends take questionable laser printers, even if they’re free. I also met some new people and made several connections, which is another important part of these events. Waiting in line could be boring, but it’s actually an opportunity to make friends with your fellow waiters.

If you’re considering attending next year’s event, try going for the whole weekend and not just Saturday. The VCF team has done a good job spreading events across the three days, and I expect they’ll continue tweaking their schedules to balance the load. Given the changes and updates they’ve implemented already over the past few years, I’m fairly confident they can handle the growth in interest and attendance. The Federation staff put in a Herculean amount of effort into the show, and it really does come through in their presentation and enthusiasm. So if you’re interested in going to the show, make a vacation out of it and enjoy everything New Jersey has to offer. Maybe I’ll see you there.