Q: Can I still use Pantone colors inside Adobe products?

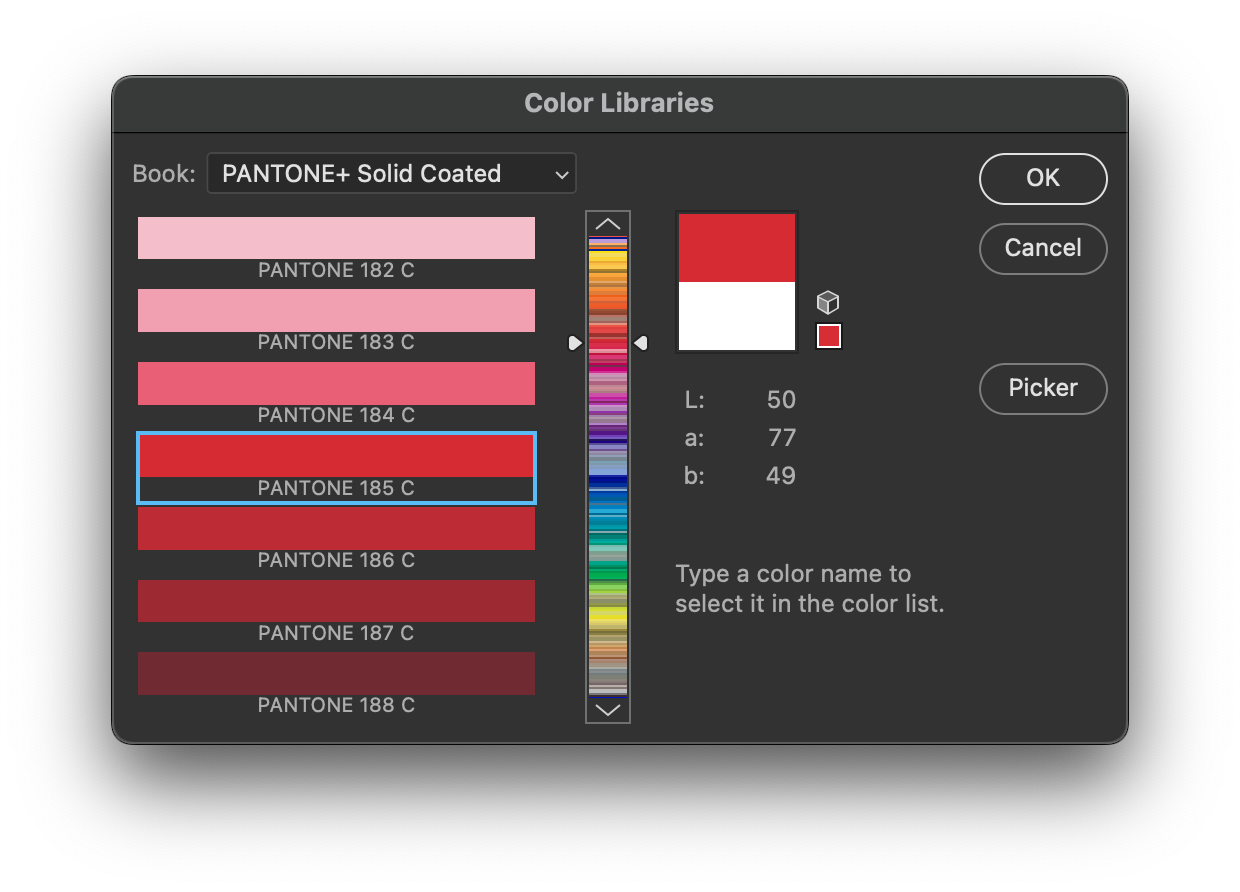

You sure can! Nothing’s stopping you from scanning a Pantone book with a spectrophotometer, writing down the LAB values, and composing your own swatch library. Perhaps you’ll, uh, acquire a library from somewhere, wink wink. You can also import old swatch libraries from older versions of Creative Cloud. Heck, you could just make a new ink, call it “Pantone 185 C” and set its alternate color value to 100% cyan. The app doesn’t care what you name it, because as far as it’s concerned that’s just another ink. When you use the library to add a swatch, the applications are copying the alternate color space values and pasting them into the ink you create.

If you were using Pantone color books to pick colors to use in CMYK or RGB colorspaces and not actually creating spot inks, you could definitely explore alternate swatch books. Of course, Pantone would prefer that you shell out $15 per month or $90 per year for their Pantone Connect plugin, a piece of software that I wouldn’t want to use even if it was free. This bloated piece of junk tries to “add value,” when all you really want is a swatch palette.

Q: What if I wanted to make my own Pantone swatch libraries and distribute them? With blackjack and hookers?

You’d be playing with fire, that’s for sure. Pantone’s a litigious company. One of my previous employers never distributed a Pantone spot color library with our workflow software because Pantone demanded an incredibly high licensing fee. Even if we wanted to build a database ourselves, using our own labor and none of Pantone’s provided resources, we would have been sued for distributing it. This led to some of our more enterprising users creating a Pantone database using our format and distributing it amongst themselves. Pantone wasn’t going to roll up to an individual shop and sue them, but I’d expect a cease and desist if you’re posting them on a website.

I can think of many ways to make a non-infringing version of the database, but at the end of the day applications and renderers do some tricks when they detect Pantone names (or variations like PMS 185 C). Another issue that you’ll run into is differing opinions on what constitutes a color. Should your database have the LAB values, or preselected RGB or CMYK values?

Q: Why do people specify Pantone colors?

Something that goes unsaid in a lot of this discourse is that color is hard. There’s an entire industry built around the difficult task of correctly reproducing color, which doing consistently has been a problem for centuries. Computer monitors and printers have magnified the problem, yes, but it’s always been there. Pantone (and its parent, X-Rite, and its parent, Danaher) is one part of the color industrial complex. How do you organize colors, anyway? Names are hard, because you’ll run out of them very quickly and that’s not including language localization. Pantone’s solution to this conundrum was numbers. When you say “I want Pantone 185 C,” every person in the chain has a Pantone book with color chips and formula guides to get you the same hue, every time. At least, that’s the idea—it’s easier said than done.

Q: How is a Pantone ink made?

Painters make different colors by mixing different paints together, and mixing Pantone inks for printing works much in the same way. If you mix a certain amount of Cerulean Blue and Cadmium Yellow paint, you’ll make green paint! But the quality of that green can change depending on the ratio of blue to yellow, let alone if you mix in any Titanium White to lighten things up a bit. The classic Pantone Matching System works in the exact same way, except instead of an artist eyeballing the color, Pantone’s guides contain formulas for recreating the same color every time from a base set of inks. Bob Ross can paint almost any landscape from a palette of fourteen colors, and you can make any one of Solid Coated’s 2,000+ shades from a set of fifteen base inks. It’s amazing how close that is, really. That’s why Pantone persists, because printers needed an agreed-upon way to make the same color every time.

Q: Okay, but I’ve seen Pantone colors written as hex values. Aren’t they the same thing?

You might’ve heard about RGB color, and maybe even CMYK color—these are the two most common color models. RGB adds colors together to create white, while CMYK subtracts them. I’m used to thinking in terms of bits, and hex values are one method of expressing those bits. 8-bit color means 256 different discrete values for a given primitive, with 0 for minimum and 255 for maximum. 255R 255G 255B is white, which is expressed in hex as FFFFFF. It can be none more white. Or can it?

Head back to your science class again and you’ll recall that the human brain perceives color by mixing the responses of various wavelengths of light. Visible light is only a tiny fraction of the entire electromagnetic spectrum, but in terms of frequencies it’s still a lot for us to measure. That chunk of the spectrum spans over 350 terahertz, which means trillions of spectral colors for our peepers to peep. When you see a red rose or a green lime, your eyes are measuring the frequencies of light reflected by those objects. But like a sound wave can have multiple frequencies, so can a light wave. Our brains perceive colors that don’t exist in the sun’s light! That’s because these colors are the result of multiple frequencies mixed together. Purple’s the go-to example, because it’s a combination of reflected red and blue frequencies. Compare that to violet, which exists as a spectral wavelength. This is all wibbly-wobbly colory-wolory stuff, and I won’t bore you with the finer details. But suffice to say that some colors can be reproduced in some media while others can’t, and translating between multiple media is often difficult.

Even if I simplify things and say that we stay within the RGB color model, it doesn’t get easier from there. A device producing RGB color is bound by the spectral properties of its red, green, and blue primitives. Those properties define its “color space,” or the gamut of colors it’s capable of producing. Take red, for example. If you have a computer, a phone, and a tablet, you could ask each to produce 255 red, 0 green, 0 blue. Depending on the manufacturers of the screens and their physical properties, you may see three different reds! One could be dimmer, the other could look more orange-ish. Without knowing the actual spectral properties of these screens, 255 just means “maximum output.” Controlling and accounting for these differences is color management.

Needless to say that you can’t specify the hex value that you entered in for your website’s color in the logo for your printed business cards. Even if you just printed them on your inkjet printer, it must be translated to a CMYK color model, and if your RGB color is too bright, it may be out of the printer’s gamut, rendering it duller than what you’d expect. Color management is out-of-scope here, but this should be enough to give you an idea of why people like an idea of a known, defined library of colors.

Q: Okay, so how did they determine those hex values?

This is the last of the technical bits, I promise. RGB and CMYK values are device-dependent. That means their color rendering is a function of the device’s ability to create (or reflect) light. You can request 255 Red on Monitor A and get a very different result than the same number on monitor B. This has been a known problem for a long time, so the handsomest scientists at the International Commission on Illumination devised the CIELab color space to describe color in a device independent way. This is the foundation of modern production color management, with ICC profiles and rendering intents and all the rest. The LAB color space describes the human perception of color, and we can map the colors our devices produce inside this uniform color space. It’s not the only device-independent space, and it’s certainly not perfect, but it’s good enough for the vast majority of us to get our jobs done.

When you go into Photoshop and choose a Pantone Solid Coated color from the swatch library, it gets converted from a LAB value defined by Pantone into your destination RGB color space. Some color spaces are bigger than others, but Photoshop will try to render an RGB value as close as possible. For most users, that destination color space is sRGB, which is a fairly narrow gamut as far as RGB is concerned.

Pantone does have their Color Bridge guide with CMYK and RGB alternate values for their colors, but they have never documented what gamuts they use to determine those values, along with other relevant color management settings.

Q: Why would Pantone and Adobe do this now? Won’t it annoy a lot of their customers?

Sure will! In fact, both sides are counting on it. You know how cable companies and broadcast networks fight it out every few years over carriage rights? This is basically the same thing. Usually those are just brinkmanship efforts that get resolved with maybe a minor blackout. But this isn’t going that way. Pantone’s had their Connect software live for a while, and Adobe’s let licenses lapse before. If you depend on Pantone colors for your livelihood, you’re gonna be coughing up the cash.

Q: I used one of these colors in my files! What will happen to them?

Unfortunately, it depends on the file and the applications you use! Illustrator files, InDesign files, and PDF files have spot colors—Pantone or otherwise—defined as a unique ink with an alternate color space. You should be able to open them up and see whatever colors you had selected in the file’s swatch palette. You can copy and paste them into a custom library or from document to document. Sometime around… CS6, I think, Adobe introduced a feature called “Book Color” where in addition to the alternate color space they would write in proprietary info that referenced ACB files. Adobe apps prefer this “book color” stuff, which might also trigger a color replacement. The behavior differs depending on the application used.

Photoshop’s a trickier case. The PSD file format has alternate color space declarations for spots, but it’s mostly for the benefit of other applications. If your spot channel lacks alternate color space info, Photoshop used to be able to locate a suitable one in its library. If those libraries don’t exist, you’ll get a very passive-aggressive dialog box warning you that the Pantone libraries are no longer available, and then the dreaded black separation.

Q: Why hasn’t a competitor taken on Pantone?

There are competitors to Pantone, but they mostly exist outside the North American sphere of influence. In Japan there’s DIC and Toyo, and in Europe there’s HKS. There’s also up-and-comers like Spot Matching System. Maybe they could use this as an opportunity to break into the market. But there’s a lot of inertia that will keep Pantone in place in North America. Said inertia has helped and harmed Pantone in the past. Pantone tried creating a new color matching and ink formulation system back in 2007 with the ill-fated Goe system. Goe used fewer base inks to make a wider variety of colors, but its ink was just as proprietary as PMS. Goe failed for a variety of reasons, but the main one was a lack of clarity on the future of PMS. Printers didn’t want to stock two sets of inks, and if PMS wasn’t going away, there wasn’t much of an incentive to change. Before that there was Hexachrome, which was Pantone’s idea to get everyone to move to a six-color printing process of CMYK plus orange and green. This also failed spectacularly because Pantone tried to keep most of the “magic” for itself. Pantone ultimately revamped the existing PMS system via the Pantone+ update, which reorganized the color guide and addressed the formulation of the existing base fifteen inks to give them some of the benefits of Goe’s base inks.

Going back to the traditional Matching System, Pantone controls many patents and formulas regarding the base set of inks used to create their colors. Nothing is stopping an enterprising ink manufacturer from creating knock-off or “compatible” inks, so long as they’re not infringing on patents. After all, Megabloks are compatible with Lego bricks. But as much as people dislike Pantone, there is a level of trust in that name and the ink manufacturers that license it. Print and manufacturing is expensive, and people don’t want to risk trashing their product because a slightly cheaper ink didn’t match.

Q: What if I wanted to switch away from Adobe software? Are there alternatives?

Serif’s Affinity line of products still include Pantone libraries, but who’s to say that Pantone won’t turn the screws on them as well? QuarkXPress still supplies Pantone libraries, but you don’t want to use Quark.

Q: Why are people getting black separations when opening up PSDs?

Photoshop does write alternate color space info into PSD files, but ironically enough doesn’t read it in certain scenarios. In the past it would do a name-based lookup and pick the value from their library. Now that the library’s gone, instead of falling back to the file’s alternate color space it gives you the passive-aggressive dialog box instead. Adobe’s apps in general have gotten aggressive about overriding a file’s internal definition for an alternate color space, and this is the result. I haven’t fully explored all the ramifications yet, but suffice it to say that you can still replace the color in the alternate color space if you have to. Most print workflows and raster image processors will still use their own libraries if you give them one of your PSD files.

Q: Will Pantone lose marketshare because of this? Or Adobe, for that matter?

It’s hard to say. Pantone will absolutely lose mindshare amongst designers and artists who used those Pantone swatch libraries as quick shortcuts. Those same customers will also curse Adobe’s addiction to rent-seeking behavior. But for actual professionals whose livelihoods depend on these standards, they’ll continue to pay while gritting their teeth. For newbies entering the field, their first exposure to Pantone colors are usually in these digital products. I wonder if they really want to lose that.

Pantone should be careful, though, because Adobe knows all too well when a controlling licensor overreaches. Microsoft and Apple made the TrueType font standard in response to Adobe’s iron-grip control over Type 1 PostScript fonts. TrueType eventually morphed into OpenType, which is the standard for font binaries today. All the same conditions are there—font shapes aren’t copyrightable, but binaries are.

I would be surprised if Pantone gets much traction on their plugin outside people who must use it or lose work. It’s lousy software at a terrible price. Piracy of swatch books will rise, and Pantone will have no one to blame but themselves. Maybe this is the kick in the pants that the print industry needs to tell Pantone to pound sand. Or maybe it’ll just be accepted as another tax on the working designer. Either way, the only color Pantone and Adobe seem to care about is green.